Fadecandy is a project that makes LED art easier, tastier, and more creative. We're all about creating tools that remove the technical drudgery from making LED art, freeing you to do more interesting, nuanced, and creative things. We think LEDs are more than just trendy display devices, we think of them as programmable light for interactive art.

- Video Introduction to Fadecandy

- Introduction by Nick Poole from Spark Fun Electronics

- Tutorial: LED Art with Fadecandy

- Tutorial: 1,500 NeoPixel LED Curtain with Raspberry Pi and Fadecandy

- Presentation slides: Easier and Tastier LED Art with Fadecandy

- LED Interaction Research with Fadecandy at Stimulant labs

Buy a Fadecandy Controller board:

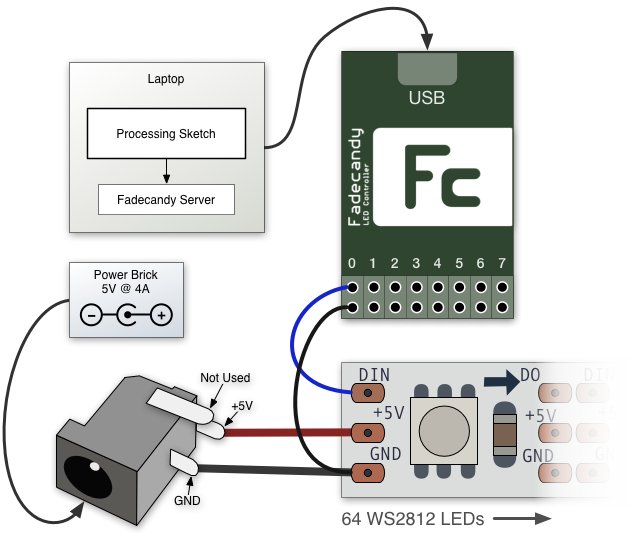

Simple Example

Here's a simple project, a single LED strip controlled by a Processing sketch running on your laptop:

// Simple Processing sketch for controlling a 64-LED strip.

// A glowing color-blob appears on the strip under mouse control.

OPC opc;

PImage dot;

void setup()

{

size(800, 200);

// Load a sample image

dot = loadImage("color-dot.png");

// Connect to the local instance of fcserver

opc = new OPC(this, "127.0.0.1", 7890);

// Map one 64-LED strip to the center of the window

opc.ledStrip(0, 64, width/2, height/2, width / 70.0, 0, false);

}

void draw()

{

background(0);

// Draw the image, centered at the mouse location

float dotSize = width * 0.2;

image(dot, mouseX - dotSize/2, mouseY - dotSize/2, dotSize, dotSize);

}A More Complex Example

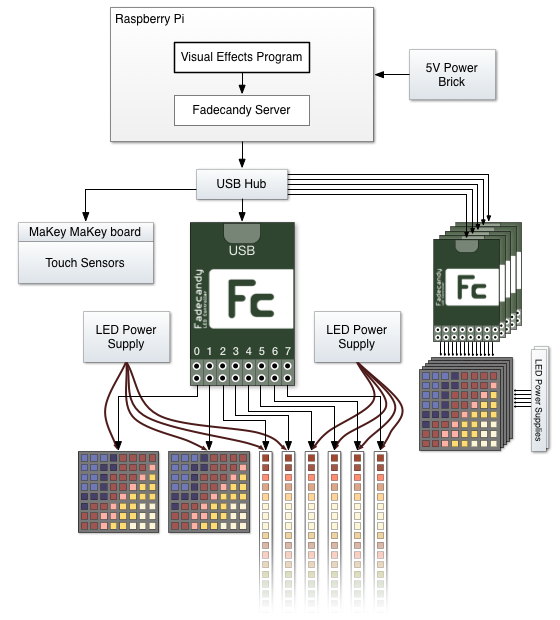

Fadecandy is also useful for larger projects with many thousands of LEDs, and it's useful for art that runs on embedded computers like the Raspberry Pi:

Project Scope

This project is a collection of reusable pieces you can take or leave. The overall goal of making LED art easier, tastier, and more creative is a broad one. To keep this project manageable to start with, there are some rough limitations on what's supported:

- LED strips, grids, and other modules based on the WS2811 or WS2812 chip.

- Common and inexpensive, available from many suppliers for around $0.25 per pixel.

- Something with a USB host port that can run your art.

- Laptops and Mac Minis work great

- The Raspberry Pi is also a great platform for this, but it requires more technical skill

- Distances of no more than 60ft or so between your computer and your farthest LEDs

- USB cables < 50ft

- WS2811 data cables < 10ft

- No more than about 10000 LED pixels total

- There's no hard limit, but it gets more difficult after this point.

These are fuzzy limitations based on current software capabilities and rough electrical limits, so you may be able to stretch them. But this gives you an idea about the kind of art we try to support. Projects are generally larger than wearables, but smaller than entire buildings.

For example, the first project to use Fadecandy was the Ardent Mobile Cloud Platform at Burning Man 2013. This project used one Raspberry Pi, five Fadecandy controller boards, and 2500 LEDs.

Fadecandy makes no assumptions about how you generate control patterns for the LEDs. You can generate a 2D video and sample pixels from the video, you can make a 3D model of your sculpture and sample a 3D shader for your pixel values, or you can create a unique system specifically for your art.

Fadecandy Controller

The centerpiece of the Fadecandy project is a controller board which can drive up to 512 LEDs (as 8 strings of 64) over USB. Many Fadecandy boards can be attached to the same computer using a USB hub or a chain of hubs.

Fadecandy makes it easy to drive these LEDs from anything with USB, and it includes unique algorithms which eliminate many of the common visual glitches you see when using these LEDs.

The LED drive engine is based on Stoffregen's excellent OctoWS2811 library, which pumps out serial data for these LED strips entirely using DMA. This firmware builds on Paul's work by adding:

- A high performance USB protocol

- Zero copy architecture with triple-buffering

- Interpolation between keyframes

- Gamma and color correction with per-channel lookup tables

- Temporal dithering

- A custom PCB with line drivers and a 5V boost converter

- A fully open source bootloader

These features add up to give very smooth fades and high dynamic range. Ever notice that annoying stair-stepping effect when fading LEDs from off to dim? Fadecandy avoids that using a form of delta-sigma modulation. It rapidly wiggles each pixel's value up or down by one 8-bit step, in order to achieve 16-bit resolution for fades.

Vitals

- 512 pixels supported per Teensy board (8 strings, 64 pixels per string)

- Very high hardware frame rate (~400 FPS) to support temporal dithering

- Full-speed (12 Mbps) USB

- 257x3-entry 16-bit color lookup table, for gamma correction and color balance

Platform

Fadecandy uses the Freescale MK20DX128 microcontroller, the same one used by the Teensy 3.0 board. Fadecandy includes its own PCB design featuring a robust power supply and level shifters. It also includes an open source bootloader compatible with the USB Device Firmware Update spec.

You can use Fadecandy either as a full hardware platform or as firmware for the Teensy 3.0 board.

Color Processing

Fadecandy internally represents colors with 16 bits of precision per channel, or 48 bits per pixel. Why 48-bit color? In combination with our dithering algorithm, this gives a lot more color resolution. It's especially helpful near the low end of the brightness range, where stair-stepping and color popping artifacts can be most apparent.

Each pixel goes through the following processing steps in Fadecandy:

- 8 bit per channel framebuffer values are expanded to 16 bits per channel

- We interpolate smoothly from the old framebuffer values to the new framebuffer values

- This interpolated 16-bit value goes through the color LUT, which itself is linearly interpolated

- The final 16-bit value is fed into our temporal dithering algorithm, which results in an 8-bit color

- These 8-bit colors are converted to the format needed by OctoWS2811's DMA engine

- In hardware, the converted colors are streamed out to eight LED strings in parallel

The color lookup tables can be used to implement gamma correction, brightness and contrast, and white point correction. Each channel (RGB) has a 257 entry table. Each entry is a 16-bit intensity. Entry 0 corresponds to the 16-bit color 0x0000, entry 1 corresponds to 0x0100, etc. The 257th entry corresponds to 0x10000, which is just past the end of the 16-bit intensity space.

Keyframe Interpolation

By default, Fadecandy interprets each frame it receives as a keyframe. In-between these keyframes, Fadecandy will generate smooth intermediate frames using linear interpolation. The interpolation duration is determined by the elapsed time between when the final packet of one frame is received and when the final packet of the next frame is received.

This scheme works well when frames are arriving at a nearly constant rate. If frames suddenly arrive slower than they had been arriving, interpolation will proceed faster than it optimally should, and one keyframe will hold steady until the next keyframe arrives. If frames suddenly arrive faster than they had been arriving, Fadecandy will need to jump ahead in order to avoid falling behind.

This keyframe interpolation is not intended as a substitute for other forms of animation control. It is intended to generate high-framerate video from a source that operates at typical video framerates.

Open Pixel Control Server

The Fadecandy project includes an Open Pixel Control server which can drive multiple Fadecandy boards and DMX adaptors. USB devices may be hotplugged while the server is up, and the server uses a JSON configuration file to map OPC messages to individual Fadecandy boards and DMX devices.

Why use Open Pixel Control?

- You can keep your effects code portable among different lighting controllers.

- OPC includes an OpenGL-based simulator, allowing you to develop effects before the hardware is done.

- The OPC server manages USB hotplug and multi-device synchronization, so you don't have to.

- The OPC server loads color-correction data into each Fadecandy board.

WebSockets Server

In addition to Open Pixel Control, fcserver also supports WebSockets, so you can write LED art algorithms and utilities in Javascript using the plethora of libraries and tools available on that platform. LED art can be easily integrated with any input device or library that will run in the browser or Node.

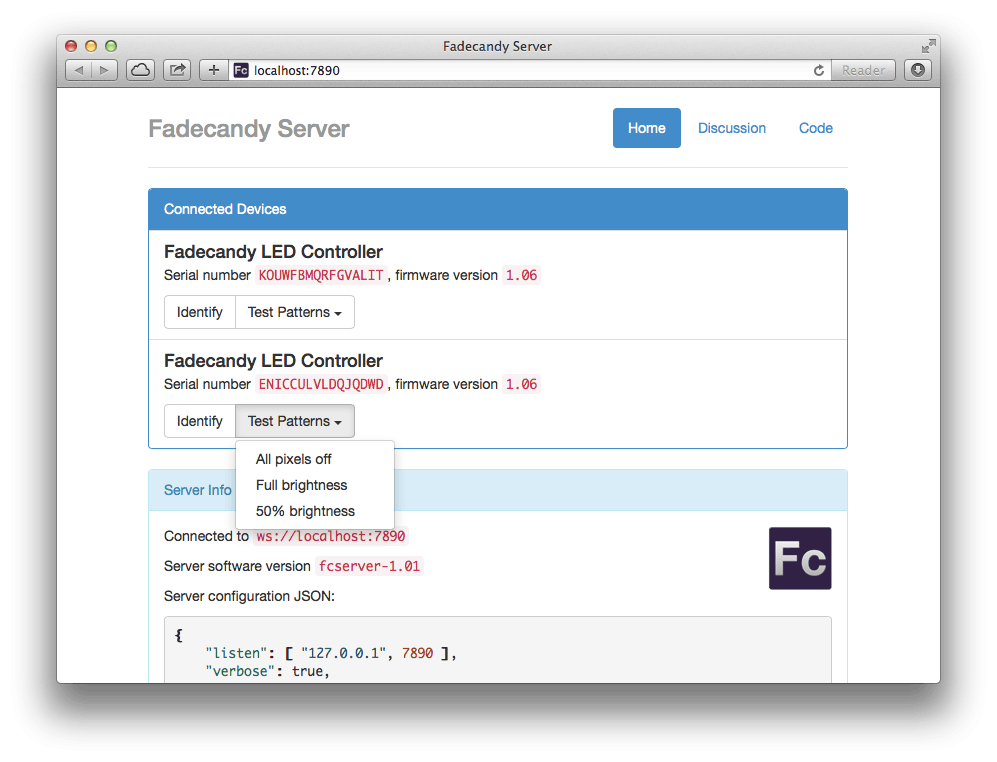

Browser UI

When you run fcserver, it also gives you a simple browser-based UI for identifying the attached Fadecandy Controllers and quickly testing your lights. By default, this UI runs on http://localhost:7890.

Where to?

- Video introduction by Nick Poole from Spark Fun Electronics

- Tutorial: "LED Art with Fadecandy"

- Sample projects are in examples

- Pre-compiled binaries are in bin

- More documentation is included in doc

- Open Pixel Control Protocol

- WebSocket Protocol

- USB Protocol

- Processing OPC Client

- Server Configuration

- ...or if you still have questions, ask the discussion group

- Buy a Fadecandy Controller board

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't you use more than 64 LEDs per strip?

This limit comes from the data rate of the WS2811 LED controller's protocol (800 kbps) and the frame rate that seems to be needed to get the best results from our temporal dithering algorithm (about 400 FPS).

With the WS2811 protocol, each bit takes 1.25 microseconds to transmit, and there's a 50 microsecond reset state that happens once per frame. Each LED has 24 bits of data. We can use this to relate number of LEDs to frames per second:

(a) fps = 1 / ( 0.00000125 * 24 * numLEDs + 0.00005 )

(b) numLEDs = floor( (1 / fps - 0.00005) / 0.00000125 / 24 )Equation (a) tells us that the theoretical maximum frame rate for 64 LEDs is 507.6 FPS. The Fadecandy Controller actually gets more like 425 FPS most of the time, since the CPU speed tends to be the limiting factor. With Equation (b), we can see that a theoretical strip length of 81 would still let us get 403 FPS. So why did I choose 64 instead of 81? Powers of two, mostly, and I honestly chose the limit of 64 before I knew exactly what frame rates would be necessary.

It would be possible to drive LED strips of around 80 LEDs in length with the same quality using a slightly more powerful microcontroller, as long as we don't rely on the strip length to be a power of two.

Will Fadecandy work on the Teensy 3.1 board?

Currently, no. The Teensy 3.1 uses a different microcontroller with a slightly different memory layout which would make it impractical to have one firmware image that's binary-compatible with both the Teensy 3.1 and the Teensy 3.0 / Fadecandy Controller board. This is a thing that's certainly doable, but I haven't wanted to spend the extra maintenance effort to maintain and test a binary image for a second architecture.

If anyone reading is passionate about supporting the Teensy 3.1 and would volunteer to maintain a port, I'd be happy to point you toward the modifications that would be necessary.

Would Fadecandy be able to take advantage of the additional processing power on the Teensy 3.1's microcontroller?

A little bit, maybe! But it wouldn't be a dramatic improvement, if we wanted to keep the exact same quality of dithering.

With some extra processing power and RAM, the strip length limit could be increased from 64 to around 80. This is hardly a dramatic increase, though. The intrinsic limits explained above are more of a factor in the design than the CPU or RAM limits.

Can you use multiple Fadecandy controllers at once?

Yes! You can use USB hubs to connect many Fadecandy boards to one controller.

What are the limits? How big can Fadecandy go?

Fadecandy limits include USB bus bandwidth, Open Pixel Control packet size, and CPU power.

USB Bus bandwidth will start to be a problem around a dozen Fadecandy boards per USB host controller. This may start to depend on the details of the computer you're using. On a laptop, each USB port will usually have an independent allocation of bandwidth available. So, connect the first dozen Fadecandy boards to one USB port, then the second dozen to another USB port, etc. If you do connect more than the recommended number of Fadecandy controllers to one port they'll still work, but frame rate will start to decrease.

The Open Pixel Control protocol used by Fadecandy has a packet size limit of 64 kilobytes, or 21845 LEDs. Any more than that will require workarounds, such as extending the OPC protocol or using multiple OPC channels.

And then there's CPU power... these limits will depend on the language and framework your code uses, and what kind of computer you're running from. A large installation with 10,000 LEDs will probably need to run off of a laptop or Mac Mini unless your code is quite efficient. Smaller installations with up to 1000 LEDs or so could run off of something as small as a Raspberry Pi. But these are very broad generalizations, and this all depends on how much processing you need to perform per-LED. Keep in mind the scalability levels of your particular framework when you plan to build a large installation.

The Raspberry Pi is kind of slow. What other small embedded Linux computers are available?

There are a lot of options to choose from, but my current favorite is the ODROID-U3. It's about the same size as a Raspberry Pi, with a 1.7 GHz quad-core ARM. There's an optional fan add-on, but I haven't found it to be necessary yet.

I'm using Windows 7, and the driver for Fadecandy doesn't load. What can I do?

Make sure you have all available Windows updates installed. Fadecandy uses a Windows feature (WCID) that wasn't present in the original retail version of Windows 7, but it was added in a subsequent update.

For reference, this is a series of screenshots showing a Fadecandy controller attached to a freshly installed Windows 7 Home Professional 32-bit virtual machine. At first it fails (no driver for "Fadecandy") but after updating Windows, it finds the correct device (WinUSB) and fcserver connects to it.

If that doesn't fix it, you may have a version of Windows with an inexplicably broken WinUSB driver. The French version of Windows 7 SP1 seems to be afflicted by this bug, and possibly others. As a workaround, you can use the Zadig utility to manually install an alternative driver. Use the arrows to change the driver on the right side of the arrow from WinUSB to libusbK, then click "Install Driver". You can see a series of screenshots illustrating this.

If you're still having trouble, please ask for help on the discussion group or bug tracker and we can get to the bottom of this problem together. Thanks for your patience!

Contact

Please direct questions to the Discussion group, it's full of smart and creative people who can help!

| Name | Size | # Downloads |

|---|---|---|

| Fadecandy_G_Schematic.pdf | 21.37 kB | 443 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Top Solder Resist.GTS | 3.58 kB | 652 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Top Silk Screen.GTO | 75.63 kB | 718 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Top Copper.GTL | 151.81 kB | 653 |

| Fadecandy_G_BOM.pdf | 27.81 kB | 401 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Mechanical 3.GKO | 256 B | 646 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Drill.XLN | 754 B | 667 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Bottom Solder Resist.GBS | 1.13 kB | 730 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Bottom Silk Screen.GBO | 66.19 kB | 1241 |

| Fadecandy_E - CADCAM Bottom Copper.GBL | 115.6 kB | 748 |

| fc64x8.sch | 459.77 kB | 931 |

| fc64x8.brd | 318.85 kB | 833 |